A little girl, wiry and dexterous, chops down thick plant stalks while her mother digs for potatoes in reddish-orange dirt, the jungle’s trees enveloping them both. Their movements are quick, efficient with long practice, yet in contrast, the camera lingers. This simple action is symbolic of the entire lifestyle depicted in Kalyanee Mam’s “A River Changes Course,” a documentary that traces the stories of three families as they struggle to make a living in modern Cambodia. People that have survived in the same way for untold generations now face difficult choices as the nation becomes more industrialized and urbanized. Also at stake is the viability of traditional vocations, which have allowed Cambodian citizens to subsist independently if not in luxury, versus occupations that pay better but require other sacrifices—separation from loved ones as well as obligation to nameless foreign employers.

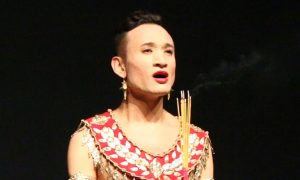

Khieu Mok, a young woman from a village outside Phnom Penh, supports her family whether by helping with the harvest or becoming a factory seamstress.

Three perspectives inform the documentary: Sari, a teenage boy who aspires to higher education while his Cham (Khmer Muslim) family makes a living by catching fish from the river they constantly float on; Khieu, a young woman from a rice-growing village but sent by her mother to a factory in the capital; and Sav, the mother shown at the beginning, in rustic northeastern territory that may soon fall to corporate clearing and redevelopment. Each of the three expresses concerns about the future, but in their own ways.

Sari understands that his prospects are limited if he remains a fisherman, but there seem to be few other opportunities. He has heard it is easy to work at a Chinese-owned cassava plantation but finds otherwise once trying it for himself, away from his family. As a good daughter, Khieu just wants her mother to be happy. Khieu does her best to improve her family’s situation by leaving them to earn $61 per month in a Phnom Penh clothing factory. She explains she is so busy that she has no time to think about the future, ultimately leaving the decision about her employment up to her mother. Sav worries about deforestation and the prospect that posterity will no longer be able to live off the land. Yet she also says her family has started using a mechanical rice huller and charging others to borrow it, yet another sign of the encroaching industrialism that threatens the old ways. All three are deeply committed to ensuring their family’s well-being, but are unsure what it will take to do so.

For long intervals, there is no dialogue or commentary, simply scenes of Cambodia’s lush landscape and people at work in its waterways and rice fields. Indeed, after a recent screening at the The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival, Mam remarked that she was struck by the country’s natural beauty upon her first visit, an appreciation that is clearly reflected in the documentary. As its director, producer, and cinematographer, Mam keeps her own voice in check, allowing the subjects to speak for themselves, though their plight is more often shown rather than told. Stylistically, this avoidance of narration re-emphasizes the audiovisuals and the evidentiary quality of the film as it captures snapshots of a society in transition.

Moments of levity punctuate the overall serious mood, as when a family watches a television commercial in which the reason the product should be bought is incongruously because “I love you!”, or when a young boy sings lyrics that promise a Lexus and a mansion or “villa” to a potential love interest. Yet even these vignettes make viewers wonder whether happiness is inextricable from material comfort and socioeconomic status, a question transcending the Cambodian context. Grains of rice and pounds of fish may be replaced by piles of sewn garments or hours of sweating on a cassava field, but the dilemma remains: what is a good job, and how does the average person provide for themselves and their family? In other words, how does one get ahead or have something to show for their labor, perhaps even joining the middle class?

There are few easy answers or strong opinions given about how to proceed, but the raw, straightforward portrayal compels us to think about these hardworking people and find parallels to our own experience. With grace and careful attention to everyday episodes from Cambodians’ livelihoods, “A River Changes Course” is ultimately a pensive look beyond three individual cases into the meaning of striving for better a life despite limited resources.